Guest writer: Björn Erik Gustavsson

Immediately after arriving in Prague, I head to the legendary Slavia café, right next to the Vltava and the National Opera.

Everything is the same as I remember it from the 1980s. The pianist plays the same kind of evergreens at the black grand piano, the waiters glide around with their trays and a little way away you can see newspapers stretched on wooden frames. The red trams rumble past outside the panoramic windows, and across the river the heights of the old town rise up towards the central castle area.

Opened in 1884, the café was long a meeting place for intellectuals. Rilke sat here and wrote poetry, and opposition figures such as Vaclav Havel gathered here during the communist era - while the secret police kept watch a few tables away. In the 1980s, surveillance cameras were installed in the ceiling.

On the surface, Slavia looks the same - but it doesn't take long to realise that everything is actually different. In the past, there were discussions, reading and writing around the tables. Now it's mobile phones, selfies and loud tourist groups.

Prague has certainly changed in recent decades. On the surface, it's still one of Europe's most beautiful cities, dominated by magnificent late 19th-century stone houses and intriguing alleyways and passageways. But the pulse is different, faster, more fashionable, the shops flashier, and the number of tourists so high that the most popular streets are barely passable during the day.

I'm staying at the stylish Mozart Prague Hotel, housed in a palace near Charles Bridge and with magnificent views of the Vltava. This is where Mozart stayed during his time in the city, where he was so successful as a composer. In the evening, I see an outstanding production of Dvorak's Rusalka at the nearby State Opera.

After another day of visiting museums and walking along almost empty alleys up the hills, in an area where much of the film Amadeus was shot, I check into the design hotel Mosaic house, with remarkably service-oriented staff and an eco-thinking that seems to permeate the whole business. Most impressive: a huge library with high ceilings just inside the lobby.

Prague is still a cheap city for Swedes, generally about 25 per cent cheaper than Stockholm. If you go to the suburbs, and the rest of the country, the price level is even lower.

Out in the countryside, the number of tourists is fairly small, with some exceptions, such as the ancient spa towns of Karlsbad and Marienbad. I myself visit the provincial town of Pardubice, an hour's journey to the east, where the inner city has retained an old-fashioned character. Near the castle there is an expansive cultural centre, housed in huge mill buildings, built in 1909 in pre-modernist style.

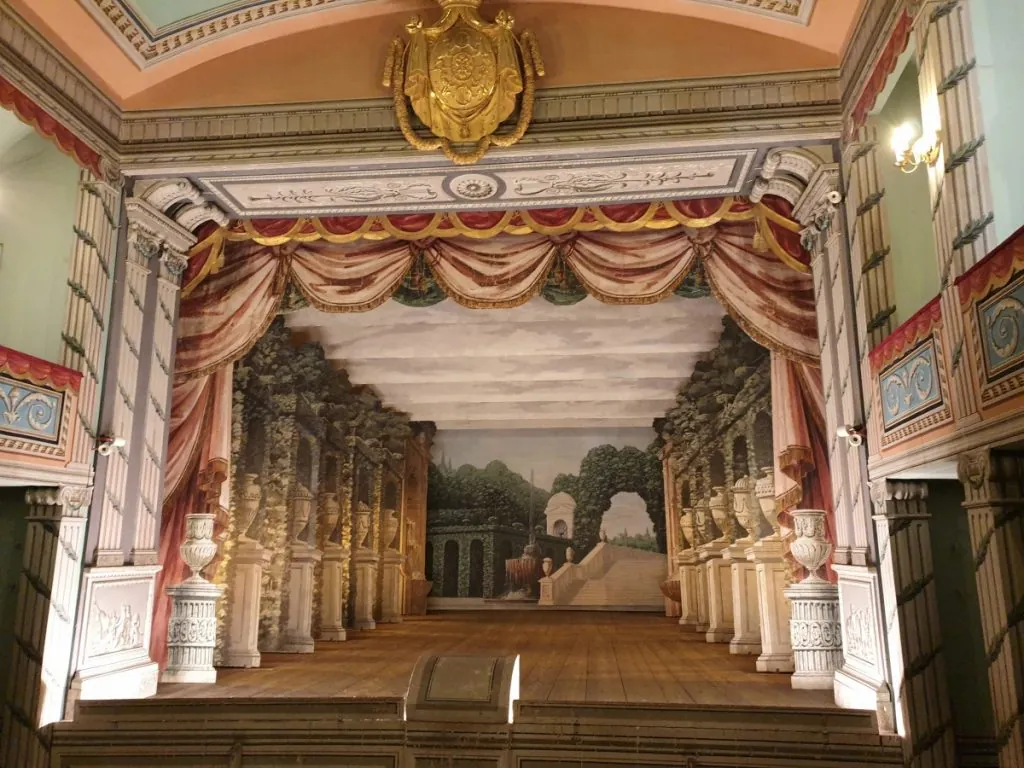

Even further afield in Bohemia - once part of the Habsburg Empire - you shouldn't miss the charming town of Litomysl, built on a hill with a medieval castle perched on top. Probably most worth seeing is the built-in, extremely well-preserved court theatre from the 18th century; in many ways similar to the Drottningholm Theatre.

To the east of the castle courtyard, you can visit the floor where composer Smetana grew up. His father was a master brewer - and on the day of his son's birth, he rolled out a large beer barrel in the square and invited people to a big party.

Litomysl is considered one of Prague's most vibrant cultural centres. There are usually events to enjoy all year round. June saw the annual Smetana Festival, an international music festival with a host of concerts - and this year it's extra special because it's the 200th anniversary of the birth of the National Romantic composer.

Wander the monastery gardens at the top of the castle and look out over the small town, or climb the tower of the cathedral - now restored after a long period of decay during the communist era, when there were metres of undergrowth along the aisles and cars parked everywhere. Just below, a 500-metre-long square stretches out, surrounded by arcades and building facades painted in soft ochre colours.

In the south of Moravia, west of Breclav, is one of the country's largest wine-growing areas. In Lednice, I visit a World Heritage-listed Renaissance castle surrounded by vast parkland - and further out in the countryside, there are great hiking and cycling trails for those who want to get up close to the Czech countryside.

In the charming small town of Valtice, I visit a restaurant set in sandstone caves and passageways where wine barrels are still stored and where, in addition to excellent wines, Moravian folk music was offered later in the evening, with musicians and dancers in colourful folk costumes.

From Breclav, which is close to the Austrian border, it's just an hour's train journey to Vienna. You'll have time to visit the classic coffee houses and get an insight into 20th-century Austrian art at the Wien Museum before it's time to take a seat at the Staatsoper, an architectural confection resplendent with ornamentation, gold and mirrors. Here was an immensely powerful Salome, Richard Strauss's groundbreaking opera, this evening with Finland-Swedish Camilla Nylund as a brilliant soloist and who made the audience shout their appreciation.

To round off the night, we stayed at the nearby Grand Ferdinand, a luxurious hotel on Ringstrasse with surprisingly moderate prices - at least compared to the legendary Hotel Sacher a few blocks away, which is probably one of the most expensive in Europe.

Text and photo: Björn Erik Gustavsson